Perspectives

ASEAN what energy future?

From exporter to importer, Southeast Asia is redefining its gas balance. Amid rising demand, expanding infrastructure, and growing competition from renewables, the challenge lies in finding a sustainable role for LNG

8 minT

he ASEAN region is experiencing a structural shift in its gas balance. Once a comfortable net exporter of LNG, it is now moving toward a tighter position as declining domestic production is increasingly offset by rising LNG imports and expanding regional pipeline trade.

A new gas balance

While overall gas consumption in ASEAN has remained stable rather than surging, the region’s role in global LNG markets is evolving. The key question is whether future gas demand will merely replace declining domestic production with imported LNG or expand enough to create a larger, more dynamic market that attracts global supply. The growing number of LNG export projects worldwide could strengthen ASEAN’s outlook—provided prices fall to levels that make additional volumes economically competitive.

Looking beyond China and India as the main engines of Asian LNG demand growth, the ASEAN nations stand out as the most promising “next tier” buyers. Collectively, they combine large populations (Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines), dense urban economies (Singapore and Thailand), and a steadily expanding appetite for energy. Over the past decade, ASEAN countries have tripled their LNG imports, reaching 37 bcm in 2024—albeit from a very low base.

In many cases, LNG is filling the gap left by declining domestic gas production—a transition complicated by the much higher cost of imported gas. After accounting for liquefaction, shipping, and regasification, LNG typically costs three to six times more than locally produced gas. Sustaining demand growth at such price levels will be difficult, particularly in the highly competitive power generation sector, where LNG must compete directly with cheaper alternatives such as coal and renewables.

Although ASEAN’s LNG market is still modest compared with global volumes, its growth potential is substantial. The ten ASEAN member states together account for just 4% of global gas consumption and 8% of LNG imports today, yet their expanding demand could meaningfully influence global trade flows—even if not entirely reshape them. Import infrastructure is developing quickly, with new projects expected to nearly double the region’s LNG import capacity by 2030. Still, the key word is *potential*. Growth in LNG demand is far from guaranteed: over the past decade, both gas production and consumption in ASEAN have declined, constrained by resource depletion and limited investment in new import infrastructure.

Thailand leads the way

Thailand has been the most dynamic LNG importer in ASEAN, accounting for roughly half of the region’s growth in LNG imports since 2011. Once almost entirely dependent on long-term contracts with Qatar, it has since become one of the world’s most active spot-market buyers. Thailand plans to add another 8 bcm per year of import capacity at Map Ta Phut, which will begin operation by 2029. Its LNG imports are complemented by pipeline gas from Myanmar and Malaysia, reflecting an increasingly diversified—and dependent—supply portfolio.

ASEAN autonomously meets about a quarter of its internal LNG demand

About one-quarter of ASEAN’s LNG demand is supplied from within the region. Malaysia and Indonesia—two of the world’s earliest LNG exporters—remain net suppliers, providing gas to both neighboring ASEAN countries and major buyers in Northeast Asia. They also export smaller pipeline volumes through the expanding Trans-ASEAN Gas Pipeline (TAGP) network, which connects national grids and supports cross-border supply balancing.

Beyond intra-ASEAN trade, the region depends heavily on imports from Qatar, Australia, and a wide range of spot-market suppliers. Notably, roughly one-third of ASEAN’s long-term LNG contracts are now signed not with producers but with portfolio players and aggregators, reflecting a shift in how regional buyers manage supply flexibility and price exposure.

The infrastructure development

A wave of infrastructure development underpins ASEAN’s LNG outlook. Vietnam, Cambodia, Singapore, and the Philippines have all invested in new import terminals, laying the groundwork for increased LNG utilization. While terminal capacity alone does not ensure proportional demand growth—global utilization rates average around 40%—it provides critical flexibility to meet both baseload and peak demand when LNG prices are competitive.

According to S&P Global, ASEAN countries currently have roughly 75 bcm per year of LNG import capacity in various stages of development, including about 25 bcm per year under construction and another 50 bcm per year planned or proposed. With imports totaling 37 bcm in 2024, the prospect of doubling regional capacity within the next decade appears plausible, even if actual utilization rates remain lower.

On the supply side, ASEAN will continue to contribute to global LNG flows

On the supply side, ASEAN will continue to play an important role in global LNG trade. Indonesia’s Abadi LNG project, operated by INPEX in the Masela Block, advanced to the Front-End Engineering and Design (FEED) stage in August 2025 and is moving toward a Final Investment Decision (FID). By contrast, the Greater Sunrise LNG project—straddling the maritime boundary between Australia and Timor-Leste—remains stalled amid disputes over whether to prioritize domestic use or exports.

The broader strategic question is whether Indonesia and Malaysia—ASEAN’s two largest gas producers—will evolve from being net LNG exporters to more balanced markets with growing import needs. For now, Indonesia continues to source most of its LNG from domestic projects and prioritize exports, relying instead on coal and renewables to meet incremental power demand. Malaysia, while still a major exporter, has begun modest imports—less than one cargo per month from Australia—and operates two regasification terminals in Melaka and Pengerang, with a third planned in Lumut, Perak. Over time, Malaysia is likely to redirect more LNG volumes to domestic use as regional gas supplies decline, even as it expands investment in solar and other renewables.

An open-ended future

Ultimately, the trajectory of ASEAN’s LNG demand will depend on its ability to remain competitive against coal and renewables. Replacing domestic gas with imported LNG is already expensive, and displacing coal is even more challenging given the wide cost differential. In many cases, subsidies or targeted policy support will be needed to make imported LNG economically viable.

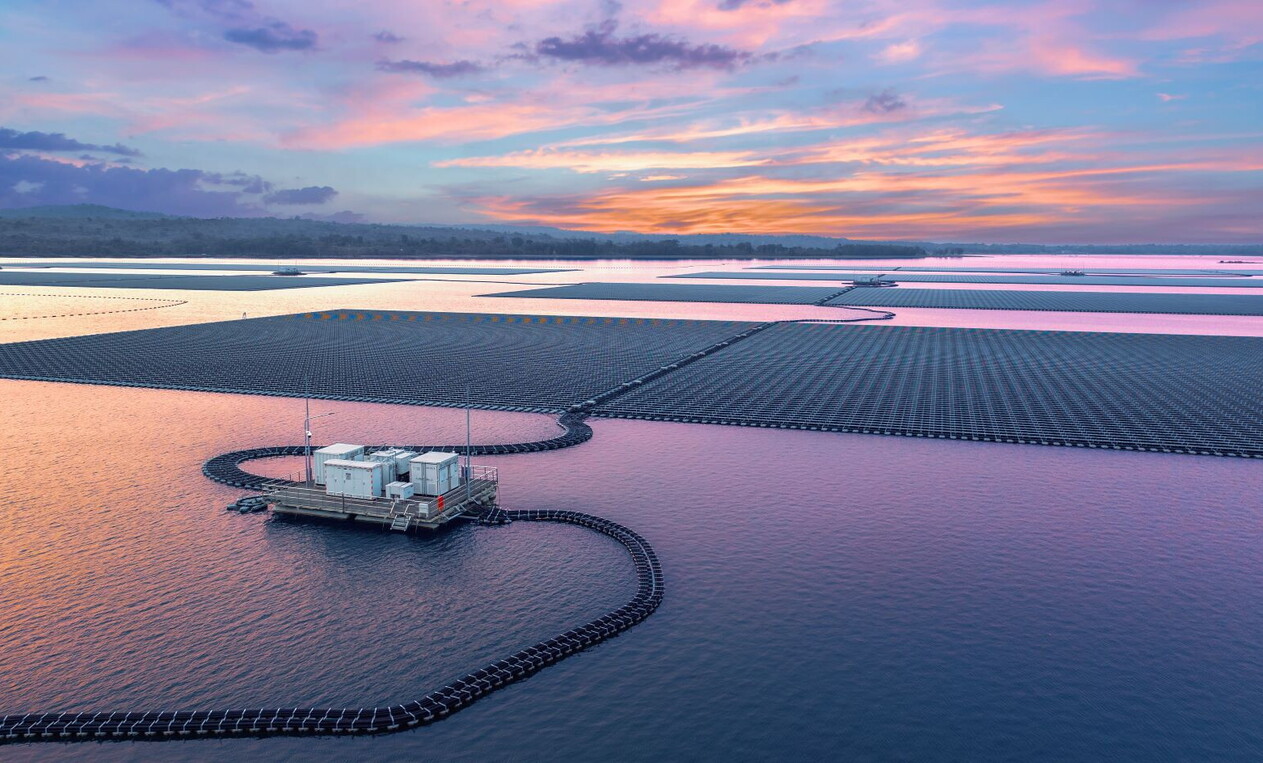

Meanwhile, renewable deployment is accelerating rapidly—especially in Vietnam and Thailand, where high solar irradiance and falling technology costs are driving large-scale solar expansion. Proximity to China reinforces this shift, as Chinese firms can supply and finance renewable projects at highly competitive rates, further eroding LNG’s market share potential. While LNG will remain important for grid balancing and flexible backup generation, its long-term role as a baseload fuel—especially at significantly higher volumes—will be increasingly hard to justify in the face of cheaper and more scalable clean energy alternatives.