Towards a new global order

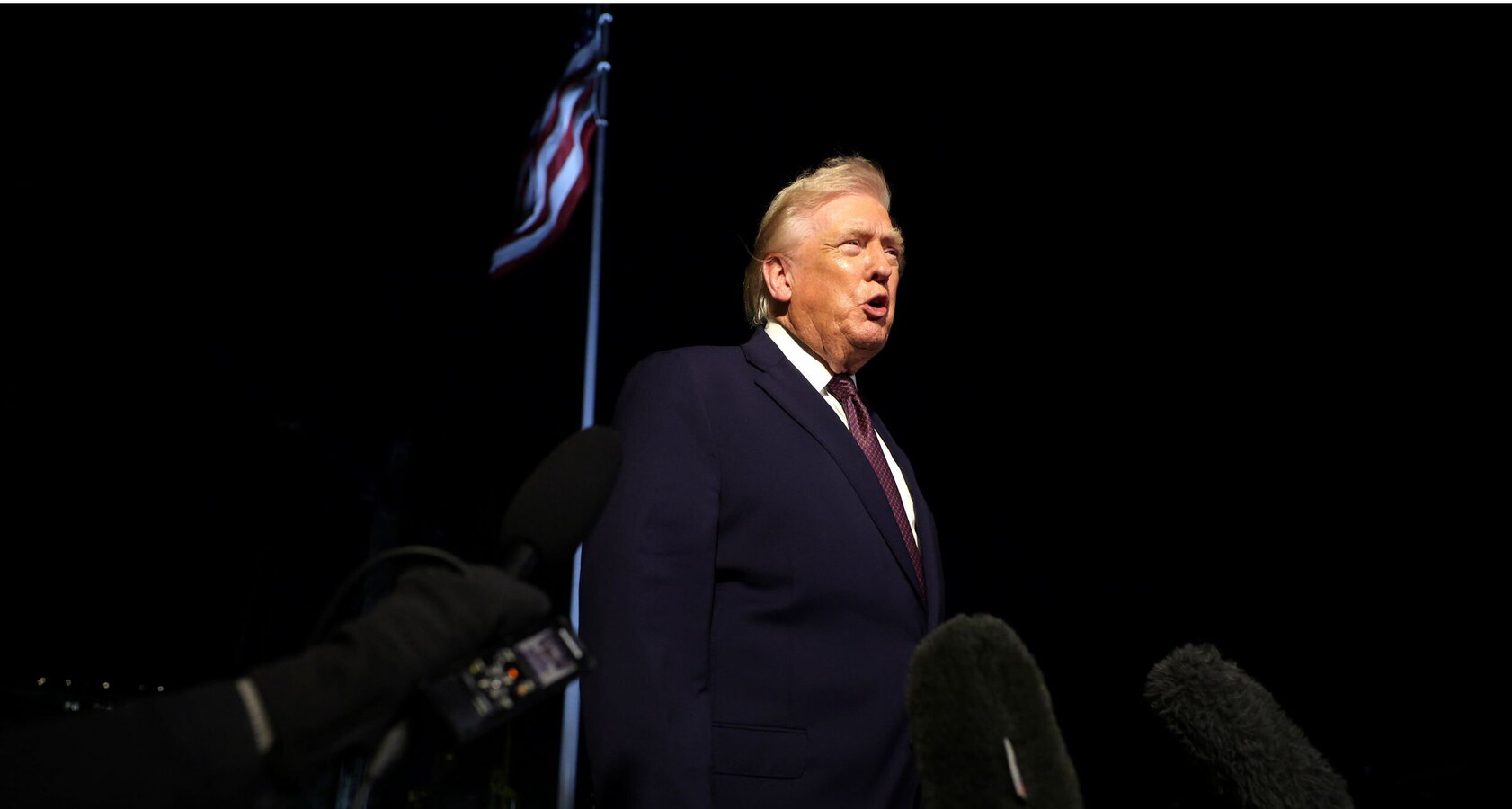

The inevitability of Trump

After 30 years of globalization and liberal illusions, the West is reckoning with its own industrial and political decline. The “realism” of the new US administration emerges as necessary response to a world out of balance

8 min

W

riting about President Donald Trump and the outcomes of his actions calls for a rare quality: boldness. Today, that quality is all too often sacrificed to political correctness and the nonsense that follows from it. Among this nonsense is the ludicrous situation where, while someone in the press or on the street is busy predicting the catastrophes and human disasters that would be triggered by Trump’s policies, what we actually see is peace imposed on Gaza and the American economy healthy against all odds, and not ruined by tariffs.

Our purpose here, however, is not to fuel the controversy surrounding the U.S. President. Instead, we seek to understand him within a framework of the world economy that had been upturned and was in crisis of balance well before he came along.

The origin of the trade imbalance with China

To understand this crisis, we need to recall in passing in this brief note how it was and is that the United States of America found itself in the absurd position of an unsustainable trade imbalance with China and a strategic crisis that Trump has merely acknowledged. And to do so, we need to go back to Clinton, the smartest president along with Nixon, whom Alan Greenspan, in his memoirs, recalls meeting. He, too, had to confront a simple fact, as the now-forgotten Mexican crisis showed: at that time, the United States found itself, given the state of its external accounts, struggling even to deal with a crisis in its economic periphery. The disaster of U.S. manufacturing—the lack of progress that amounted to regression when compared with the economies of Europe, Japan and later the Asian tigers—left no room for hope.

The solution devised by him and the other architects of U.S. policy was to open up to China despite Tiananmen Square. The calculation? Simple, the very same one that had filled London and Washington with enthusiasm in the 1920s, but which Mao had ruined: entrusting China with production at the lower end of the value chain, while keeping technology and finance for itself and re-centering American leadership around them. Ditching manufacturing—and that part of the U.S. that depended on it to survive—in favor of the Internet and Wall Street bubbles.

The path to domestic deindustrialization began. Investment flowed into the People’s Republic, allowing it to multiply its share of global manufacturing output. The result was deflationary commodity prices that reabsorbed Wall Street’s speculative inflation and neutralized the reckless printing of yen and then dollars and finally euro with the falling prices, driven by the boom in China. The myth of growing tertiary productivity, which is questionable, given the statistical definition of this sector—or the foolish reassurance that the West were holding on to the high end of the value chain. This was coupled with the lie about the market supposedly shaping China into a democracy, which did the rest. German car factories in China, Italian machines for making shoes or wraps and so on: for thirty years, Europe and the West have stubbornly demolished their industrial production—the only thing capable of guaranteeing serious increases in productivity. What remains in Europe has been profoundly renewed, perhaps more so than in America. But in the meantime, an unproductive service sector has run rampant, while bureaucratic madness of the EU has peaked in the craze for a miscalculated energy transition. And lo and behold, China has conquered hegemony and with it, despite Clinton’s calculations for the United States, the top of the value chain.

Trump’s necessary reaction

Few are willing to do the real math. But there is no need for percentages: the disaster of the West and Europe is quite obvious. As is its instability, which is the desperation to make a 180° turn, as if nothing had happened, from the terror of the greenhouse effect to the production of weapons. Let’s line up these 30 years: the rhetoric of both Clinton and the euro and Europe now proves to have failed. Discredited by China as by each of the vital crises that this reckless opening up of the markets has caused. The influx of low-productivity migrant labor is the final blow to hopes of reviving per capita growth: a disaster, bringing political upheaval that is now inevitable.

President Donald Trump—not simply “Trump,” as some newspapers write, with a hint of contempt— offers a needed reaction to a China that would otherwise end up dominating every sector. His is a gesture that comes even before the inevitable downward trajectory of Asian economies, which are destined to slide into deflation after the boom. It’s now or never: President Trump knows it. His actions restart the cycle of the world economy, which is not only one of booms and busts, but is also one of liberalism and mercantilism. In the 1930s, the UK locked itself up in its Empire, as Roosevelt’s America did in its protectionist bubble, which built-up gold reserves and ended up ruining what was left of multilateralism and growth. But then, having won the war, Washington used its loans to blackmail the British, forcing them to dismantle imperial preference.

The story is always the same: a struggle for power to which the rhetoric of economists and newspapers and their hatreds always conform in the end. Opinion-makers are out of step, out of time in their obedience to platitudes. They have failed to understand that Clinton’s idea of globalization has failed, just as—for different reasons—Mitterand’s idea of the euro failed, as the record now shows, to contain Germany. And yet, it is precisely Germany that is rearming within its historic geopolitical borders: the Baltic and Ukraine: another paradox that people prefer not to think about. Instead, everyone remains intent on judging, on distinguishing between good and bad, on looking back.

There has been no progress, promises have not been kept: under the pretext of moving forward, we have created a more unjust and disordered world. It matters little to those who continue to look to the past, tormenting us with their judgments. The answer is always the same: there has not been enough progress. But sooner or later Europe too —like China and Russia— will have to adopt Trump’s realism, whether conformists —always out of step with the times— like it or not. European nations will have to abandon the failed rhetoric of the globalizers and learn from Trump’s boldness.