Silent revolution

The new LNG diplomacy

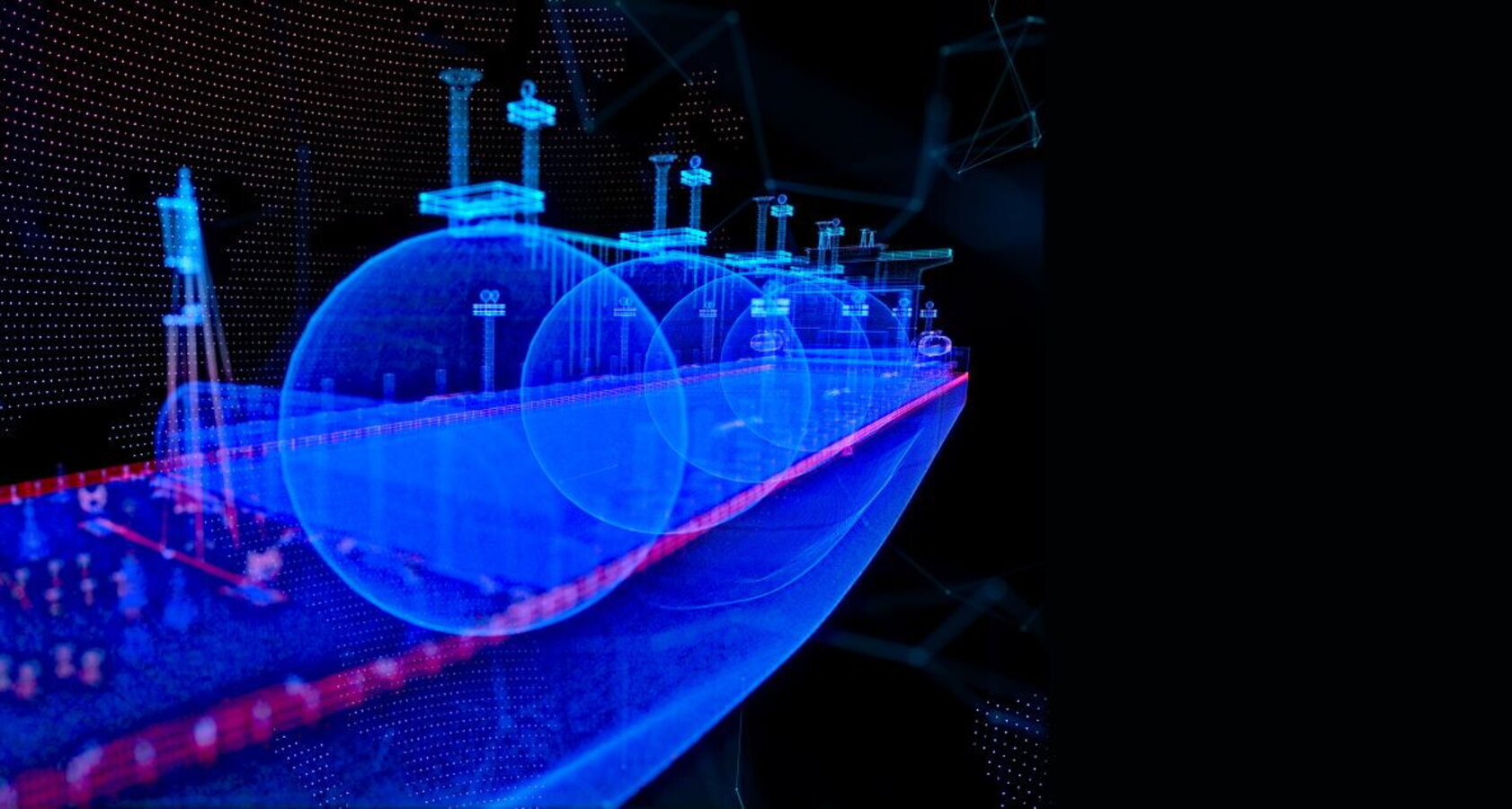

From Jakarta to Manila, energy choices are becoming strategic decisions. LNG carriers, terminals, and pipelines are replacing traditional instruments of influence. LNG has now become a political currency in power rivalries

6 minI

n Southeast Asia, a quiet revolution is unfolding—not driven by ideology or insurgency, but by molecules. By liquefied natural gas (LNG). Once a niche fuel traded among a few wealthy nations, LNG has become a lever of influence, a bridge to energy security, and a pawn in an increasingly high-stakes geopolitical game.

The stakes are high. As Southeast Asia’s cities expand and its industries surge, the region has become the epicenter of global LNG dynamics. From the glass towers of Kuala Lumpur to the ports of Batangas and the rice fields of Java, the future of the world’s gas trade is being redrawn—not by grand theories, but by tankers, terminals, and power plants.

This is not just a story of supply and demand. It’s a story about power — economic, political, and strategic. LNG is both a weapon and a currency. It buys time for developing economies trying to transition from coal to cleaner fuels. It buys influence for exporting countries seeking leverage. It buys friends for powers locked in global rivalry.

Old and new players

Consider Indonesia and Malaysia. They are not just exporters, but incumbents. For decades, their LNG has fueled the furnaces of Japan, South Korea, and, more recently, China. Now they face a double challenge: sustaining export revenues while meeting fast-rising domestic demand. The math is unforgiving—every unit burned at home is one less shipped abroad.

In Jakarta, energy officials invoke “national resilience.” In Putrajaya, planners wrestle with subsidies and political timing. Both walk a tightrope—between global markets and local voters, between long-term contracts and short-term populism.

Meanwhile, new players—Vietnam, Thailand, and the Philippines—are entering the LNG arena not as exporters but as hungry new buyers. Their power plants are rising, their terminals fast-tracked. Their demand is no longer theoretical; it is inevitable.

Enter the Americans. Flush with shale gas and hungry for markets, the United States has deployed not just LNG cargoes but diplomacy. Ambassadors promote terminals. Energy secretaries pitch contracts.

Statecraft now includes spreadsheet projections and regasification diagrams

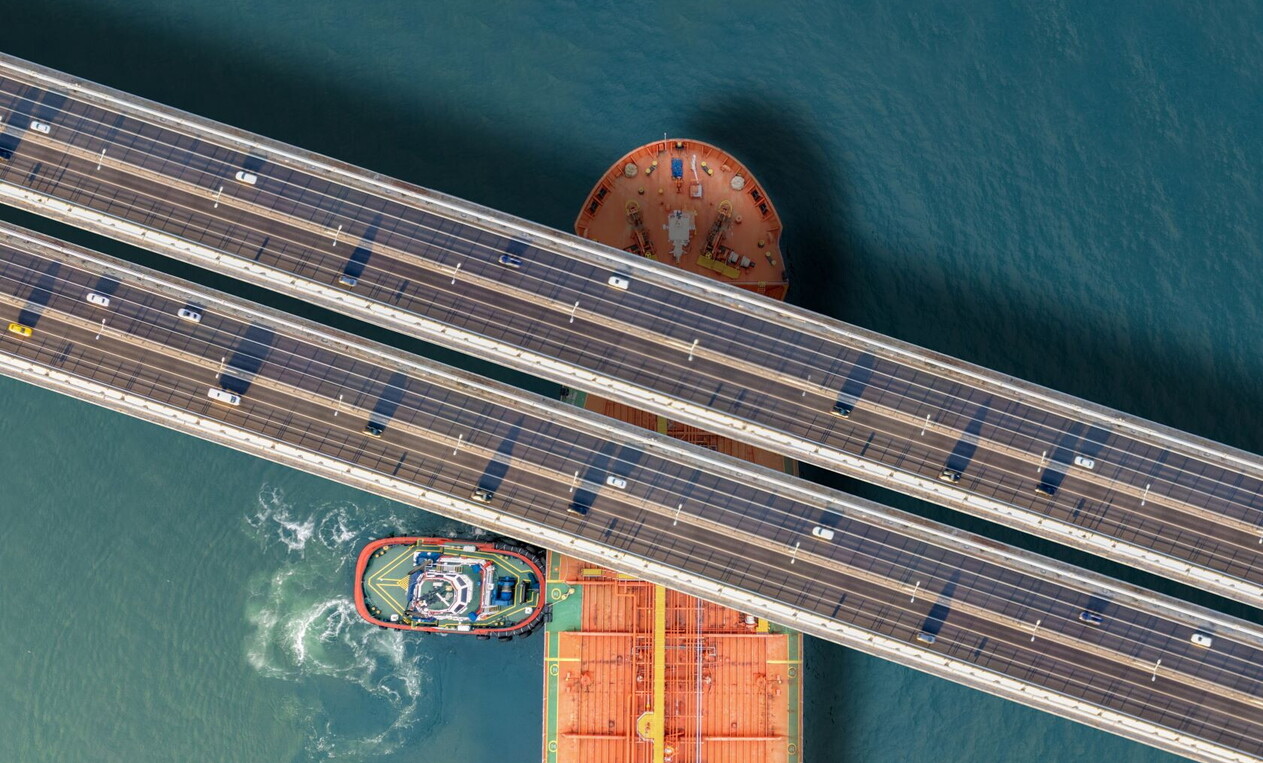

And China is not standing still. As the region’s biggest buyer, it is also its most strategic. Beijing understands what Washington is only beginning to grasp: that LNG is infrastructure — and infrastructure is influence. By investing in shared pipelines, terminals, and port access, China is binding its neighbors not just economically, but geopolitically.

This is the new reality: energy deals are no longer just about price per MMBtu. Price still matters of course, but so do ports, politics, and projection. Every terminal built with Chinese financing is a node in a network. Every long-term contract signed with a U.S. exporter is a commitment to a global alignment.

And Europe? Still recovering from its energy trauma after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it watches this theater with growing anxiety. European policymakers now understand what Southeast Asia has known for years: that energy dependency is vulnerability. As the continent diversifies its gas supply, it too must choose between Atlantic and Asian ties. And this choice is not technical. It is political. And the window for neutrality is closing.

The infrastructure geopolitics

What makes Southeast Asia different — and dangerously underappreciated — is the speed of change. While debates in Brussels and Washington can drag on for years, decisions in Manila or Hanoi are made and implemented in months. Infrastructure is being built. Contracts are being signed. Alliances are taking shape — sometimes quietly, often decisively.

And this speed creates asymmetries. It tilts the playing field toward those who are present, agile, and persistent. It punishes hesitation. It rewards the kind of diplomacy that understands a megawatt-hour can speak louder than a communique.

This isn’t just about gas. It’s about the kind of world we are heading toward — one where the front lines of competition are not just military or technological, but infrastructural. Where pipelines matter as much as patrols, and where regasification terminals become the new embassies.

In this emerging order, Southeast Asia is not a passive recipient. It is an active arena. Its choices — and they are choices — will shape the balance of power not just in Asia, but globally. LNG is just the accelerant.

So, watch the tankers. Track the terminals. Follow the contracts. That is where you will find the new geopolitics taking shape — molecule by molecule, deal by deal, degree by degree.