The energy of intelligence

From Cinderella to queen of the ball

In a world that is racing towards artificial intelligence and trying to shake off the burden of coal, natural gas has become no longer a second-rate resource, but the vitamin of thinking machines

6 minF

or years, gas was oil’s poor relative—the one no one invited to the party. A classic industry joke now sounds absurd: “I’ve got good news and bad news. The bad news is we didn’t find oil. The good news… is we didn’t find gas either.”

So burdensome to handle and costly to move, gas was once considered worse than coming up dry. Even today, in some regions, it still trades at a discount—or is simply flared because transport is too expensive. But times are changing. Natural gas has gone from Cinderella to queen of the global energy ball, recast as the linchpin of the energy transition, the fuel of digitalization, and the backbone of artificial intelligence.

If oil powered mass motorization, gas will drive the rise of non-biological intelligence. It is the energy of a new industrial revolution, standing by until fusion delivers its own Menlo Park moment. Among fossil fuels, gas has the highest energy density, a comparatively low environmental impact, and a versatility that makes it essential both for power generation and for industry and chemicals. Gas-fired plants can handle peaks with ease and sustain baseloads reliably; they combine the flexibility of a cross-country skier with the speed of a sprinter.

But there is one problem: it is a gas, and like all light things, it is hard to move. Scale and infrastructure are essential—compression, liquefaction, storage. For decades, this kept gas confined to local markets. In the 1930s, the United States built the world’s most extensive domestic pipeline network—240,000 km by 1940—making gas the silent fuel of the New Deal through long-distance transport. In Europe, Western Siberia supplied energy for decades, later joined by domestic production in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Norway, and eventually by new flows from Africa and the Baltic pipeline—the only major line disabled by an underwater attack that put it permanently out of service.

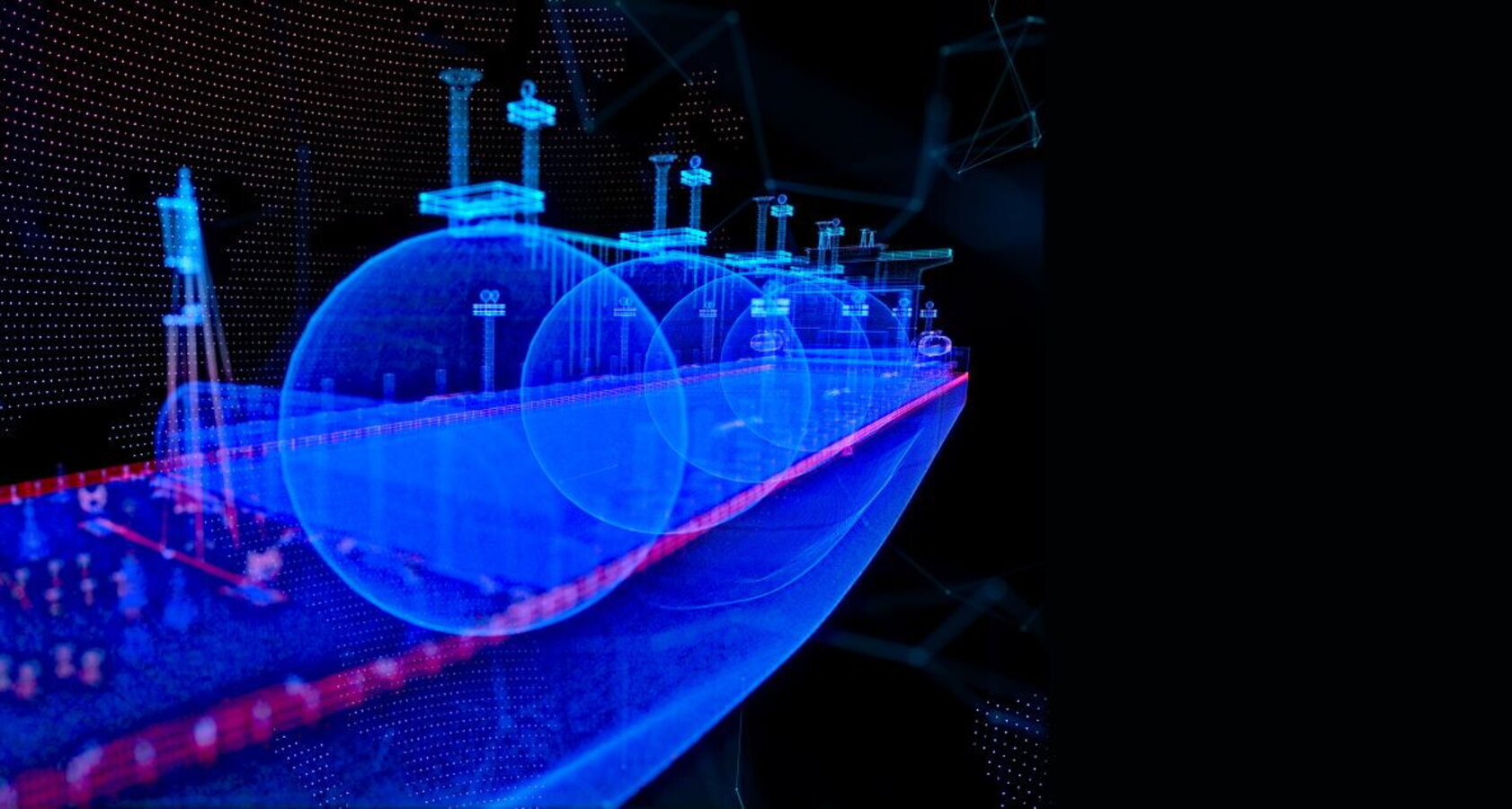

The decisive leap for the global gas market came in the 1970s with the liquefaction revolution: cooling gas to –160 °C produced liquefied natural gas (LNG), compressible and transportable by ship. The first route opened in 1964 between Algeria and the UK, but it was Asia that turned LNG into a global business. Japan and South Korea emerged as the first major importers, while Indonesia and Malaysia became key suppliers—roles that would remain strategically important for decades.

Since the 2000s, the U.S., Europe, and Asia have gradually merged into a single market, tied together by a growing fleet of methane tankers chasing arbitrage opportunities. Two very different countries shaped this history. On one side, the United States, which discovered through fracking that it had more gas than it could consume at home; by converting import terminals into export hubs, it became the world’s largest LNG seller. On the other side, Qatar, a Gulf state without vast oil reserves but blessed with North Field—the world’s largest gas deposit, shared in part with Iran—which it has turned into a cornerstone of its prosperity.

Qatar and the United States now vie almost every year for the top spot in global LNG sales

Thus LNG became the backbone of global methane trade, growing from under 150 Mt in 2000 to 250 Mt in 2010, more than 540 Mt in 2025, and a projected 700 Mt or more by 2030. Asia will drive future growth: 4.7 billion people—more than half of humanity—consume gas at per-capita levels still 8 to 10 times lower than Europe’s. With rapid industrialization and an expanding urban middle class, gas offers the fastest and most practical path to replace coal while keeping electricity supply stable. The sheer scale of Asia’s industrial systems and energy demand means its transition will not rest on renewables alone but will be powered by gas, pushing coal off the energy table for good.

This is the backdrop for Eni’s major 2023 offshore discovery in Indonesia’s Kutei Basin. The Geng North field, with reserves of about 5 trillion cubic feet (150 billion cubic meters), is more than a geological find: it anchors a new strategic alliance. Through a joint venture combining Eni’s assets with those of Malaysia’s Petronas, the partners plan to develop this field and pursue additional resources across Indonesia and Malaysia.

The old explorer’s joke has been left behind. Today, if he returned with good and bad news, the good news would be that he had found gas. The bad news? That we will need far more of it.

In a world racing toward artificial intelligence and struggling to cast off coal, gas has become the energy of intelligence—no longer a second-rate fuel, but the vitamin of thinking machines.